Musical instrument: yue

(龠)

(龠)

compiled by David Badagnani (rev. 11 January 2024)

In an effort to make this information more accessible, this document contains resources related to the Chinese musical instrument flute called yuè (龠, 籥, or occasionally also 𠎤, the former being the earliest spelling), an oblique end-blown flute, played in a similar manner to the Turkish ney or Bulgarian kaval, which appeared in Chinese culture as early as the Neolithic period.

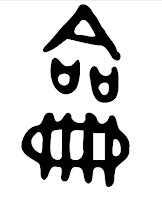

The modern character's construction has four parts: 人 + 一 + 口口口 + 冊, presumably depicting fingers (冊) pressing on finger holes (口).

The reconstructed Middle Chinese pronunciation is /jɨɐk̚/ (Zhengzhang) and the reconstructed Old Chinese pronunciations are /*lewk/ (Baxter-Sagart) or /*lowɢ/ (Zhengzhang).

According to Eastern Han Dynasty sources, 籟 (lài) was another name for the yue.

● Erya《尔雅》(Warring States, Qin, and Western Han Dynasty)

《爾雅·釋樂》

● Jiu Tang Shu《旧唐书》(The Old Book of Tang), also known simply as Tang Shu《唐书》(The Book of Tang)

Additional Web resources

Ancient forms of the character for yue.

Left: oracle bone script (used in the late 2nd millennium BC, mainly during the late Shang Dynaty)

Center: bronze script, used from the Shang dynasty (2nd millennium BC) to the Zhou dynasty

(11th century BC-3rd century BC)

Right: small seal script, based on the script of the state of Qin, systematized by Qin chancellor

Li Si (李斯) c. 220 BC and standardized by the Eastern Han Dynasty scholar Xu Shen (许慎)

in his Shuowen Jiezi《说文解字》, which was completed in 100 AD, and presented posthumously to

Emperor An of Han by Xu's son in 121 AD

According to Eastern Han Dynasty sources, 籟 (lài) was another name for the yue.

Ancient yue with five, six, seven, and eight finger holes, all made from the ulnas (wing bones) of red-crowned cranes (Chinese: danding he, 丹顶鹤), some showing evidence of ancient repair or ancient fine pitch adjustment, and dating to approximately 7000 BC-5500 BC, during the Neolithic period, were excavated between the late 20th and early 21st centuries from the Jiahu archaeological site (贾湖遗址) in Jiahu Village (贾湖村), Beiwudu Town (北舞渡镇), Wuyang County (舞阳县), Luohe (漯河市), central Henan province, central China. These instruments measure between 6.81 and 9.69 in. (17.3 and 24.6 cm) in length, and have a diameter of between 0.35 and 0.68 in. (0.9 and 1.72 cm). The red-crowned crane is among the largest cranes, typically measuring about 5 feet tall, with a wingspan measuring between 7 and 8 feet.

Specimens of such Neolithic yue having been found at two different archaeological sites, they are referred to either as Jiahu gu di (賈湖骨龠, as discovered at the Jiahu archaeological site in Henan province) or Xinglongwa gu yue (興隆洼骨龠, from Aohan Banner, Chifeng, southeastern Inner Mongolia).

Yue with three finger holes were used in the court ritual music of the Zhou Dynasty, and continued in subsequent dynasties (and, indeed, all the way to the present day) to be used as a ritual implement in the dance accompanying Confucian ritual music.

Two chou (籌) players from the Daxiangguo Temple Buddhist Music Ensemble (Daxiangguo Si Fanyuetuan,

大相国寺梵乐团), which is based at Daxiangguo Temple (Daxiangguo Si, 大相国寺), a historic Buddhist

temple in Kaifeng, east-central Henan province, central China. Photo probably taken in 2011.

Similar instruments that are still used today in China include the chóu (籌), a rare bamboo flute that used to be used in Huangmei opera accompaniment and continues to be used in Buddhist ceremonial music of Henan province; the kexiju'er (克西举尔) or kexizhu'er (克西竹尔) of the Yi ethnic group of Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture (凉山彝族自治州), southern Sichuan province, which is called yaodi (咬笛, literally "bitten flute") in Chinese, owing to the fact that it player anchors the rim of the blowing end between two of their top incisors while playing; and the yīngdí (鷹笛), a flute made from the wing bone of an eagle, which is used by the Tajik people of western China.

Contemporary performers who have worked to reconstruct and revive the ancient yue include the following:

● Mr. Liu Zhengguo (刘正国, b. Wuwei, Wuhu, southeastern Anhui province, east-central China, 1951), a professor from Shanghai Normal University who named this instrument after researching it since the early 1990s as "Jiahu bone yue" (Chinese: Jiahu gu yue, 贾湖骨龠). In 2015 he published a book entitled Zhongguo Gu Yue Kaolun《中国古龠考论》(Research on Chinese Ancient Yue)

● Mr. Yu Dongshen (于东波, b. Rudong County, Nantong, southeastern Jiangsu province, east-central China, 1981), who plays dizi, xiao, xun, and yue with the Nanjing Chinese Orchestra (南京民族乐团), and who is a protegé of Liu Zhengguo

● Mr. Chuai Zimo (揣子摩), a Bilibili user from China

It is presumed that the end-blown vertical flute called xiao (箫) or dongxiao (洞箫), with its U-shaped or V-shaped mouthpiece notch, represents a later development of the yue (the rim of the yue's blowing hole not having any kind of notch).

Links to textual sources are highlighted in green.

----------------------------------------------

Chinese historical reference works discussing the yue

● Erya《尔雅》(Warring States, Qin, and Western Han Dynasty)

《爾雅·釋樂》

「大籥謂之產,其中謂之仲,小者謂之箹。」

https://ctext.org/er-ya/shi-yue/zh#n38390

● Zhou Li《周礼》(The Rites of Zhou) (probably Western Han Dynasty)

● Zhou Li《周礼》(The Rites of Zhou) (probably Western Han Dynasty)

「笙師:掌教吹竽、笙、塤、龠、簫、篪、笛、管,舂牘、應、雅,以教祴樂。凡祭祀、饗、射,共其鐘笙之樂,燕樂亦如之。大喪,廞其樂器;及喪,奉而藏之。」

● Shuowen Jiezi《說文解字》(Eastern Han Dynasty)

「龠:樂之竹管,三孔,以和眾聲也。从品、侖。侖,理也。凡龠之屬皆从龠。」

● Shuowen Jiezi《說文解字》(Eastern Han Dynasty)

「籟:三孔龠也。大者謂之笙,其中謂之籟,小者謂之箹。从竹賴聲。」

https://www.shuowen.org/view/2979

「籟:三孔龠也。大者謂之笙,其中謂之籟,小者謂之箹。从竹賴聲。」

https://www.shuowen.org/view/2979

● Fengsu Tongyi《风俗通义》(Comprehensive Meaning of Customs and Mores or Comprehensive Meaning of Customs and Habits)

Also known as Fengsu Tong《风俗通》, this book was written by the politician, writer, and historian Ying Shao (应劭), who was a long-time close associate of Cao Cao, around 195 AD, during the late Eastern Han Dynasty. The manuscript is similar to an almanac, which describes various strange and exotic matters of interest to the literati of the period, such as folk cultural practices, legends, mystical beliefs, and musical instruments. There were originally a total of 30 chapters, but only 10 remain. These chapters were recompiled by the Northern Song scientist Su Song (苏颂) from the works of Yu Zhongrong (庾仲容) and Ma Zong (马总). Some fragments of the lost chapters exist as quotations in other Chinese texts. The yue is discussed in the《聲音》chapter, as follows:

籥:

謹按:《周禮》:「籥師氏掌教國子吹籥。」《詩》云:「以籥不僣。」籥、樂之器竹管三孔,所以和眾聲也。

Additionally, the lai is discussed as follows:

籟

謹按:《禮·樂記》:「三孔籥也。大者謂之產,其中謂之仲,小者謂之箹。」

● Shiming《释名》(Explanation of Names)

A dictionary employing phonological glosses, which is believed to date from c. 200 AD, during the Eastern Han Dynasty. There is controversy whether this dictionary's author was Liu Xi (刘熙, fl. c. 200 AD) or the more famous Liu Zhen (刘珍, d. 126 AD). The yue is discussed in the section entitled "Explanation of Musical Instruments" (Shi Yueqi, 释乐器), as follows:

「籥,躍也,氣躍出也。」

https://ctext.org/shi-ming/shi-yue-qi

A dictionary employing phonological glosses, which is believed to date from c. 200 AD, during the Eastern Han Dynasty. There is controversy whether this dictionary's author was Liu Xi (刘熙, fl. c. 200 AD) or the more famous Liu Zhen (刘珍, d. 126 AD). The yue is discussed in the section entitled "Explanation of Musical Instruments" (Shi Yueqi, 释乐器), as follows:

「籥,躍也,氣躍出也。」

https://ctext.org/shi-ming/shi-yue-qi

This historical work in 200 volumes was completed in 945, actually during the Later Jin (后晋) Dynasty, one of the Five Dynasties during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (五代十国) period following the fall of the Tang Dynasty. It is one of the Twenty-Four Histories (二十四史). The yue is discussed in Volume 29:

卷二十九

Volume 29

音樂二

「管三孔曰龠,春分之音,万物振跃而动也。」

---------------------------------------------

Chinese poems mentioning the yue

《景星》

作者:无名氏(汉)

Anonymous (Han Dynasty)

景星显见。信星彪列。

象载昭庭。日亲以察。

参侔开阖。爰推本纪。

汾脽出鼎。皇祜元始。

五音六律。依韦飨昭。

杂变并会。雅声远姚。

空桑琴瑟结信成。四兴迭代八风生。

殷殷钟石羽龠鸣。河龙供鲤醇牺牲。

百末旨酒布兰生。泰尊柘浆析朝酲。

微感心攸通修名。周流常羊思所并。

穰穰复正直往宁。冯蠵切和疏写平。

上天布施后土成。穰穰丰年四时荣。

More information:

---------------------------------------------

Bibliography

● Liu Zhengguo 刘正国. Zhongguo Gu Yue Kaolun《中国古龠考论》[Research on Chinese Ancient Yue]. Shanghai: Shanghai Joint Publishing 上海三联书店, 2015.

---------------------------------------------

Additional Web resources

● Ancient Chinese bone flutes (贾湖骨笛 / 贾湖骨龠 / 贾湖骨籥 / 兴隆洼骨龠) YouTube playlist (maintained by David Badagnani)

● Article about the chou (籌), as used by the Daxiangguo Temple Buddhist Music Ensemble (Daxiangguo Si Fanyuetuan, 大相国寺梵乐团), which is based at Daxiangguo Temple (Daxiangguo Si, 大相国寺), a historic Buddhist temple in Kaifeng, east-central Henan province, central China (China News Network, October 18, 2011):

https://www.sohu.com/a/20560587_121207

https://www.sohu.com/a/20560587_121207

● Video of the Daxiangguo Temple Buddhist Music Ensemble (Daxiangguo Si Fanyuetuan, 大相国寺梵乐团), which is based at Daxiangguo Temple (Daxiangguo Si, 大相国寺), a historic Buddhist temple in Kaifeng, east-central Henan province, central China, featuring a player of the chou (籌) (filmed October 22, 2017)

● Article about yue player and scholar Liu Zhengguo (刘正国)

---------------------------------------------

Thanks to Lin Chiang-san and Wang Hong for assistance with this page.

---------------------------------------------

Site index: